Editor's note: This was Part 1 of a two-part series of articles about 'Potato-gate.' Part 2 will publish next week and you'll be able to find it in The Vault.

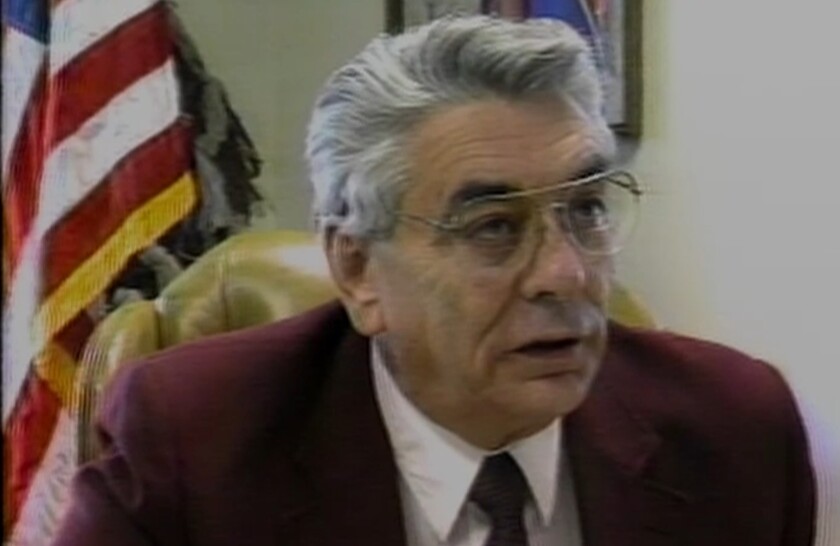

BISMARCK — Looking back, Sarah Vogel might not have run for state agriculture commissioner in 1988 if there hadn’t been a government scandal over potatoes. She liked her formidable opponent, Kent Jones, who was brought low in an international trade scandal she called “Potato-gate.”

“I might not have won the election but for that. Kent had a good heart. And then along came the Potato-gate,” Vogel, a lawyer who ended up winning the 1988 election and served as state commissioner of agriculture until 1997, said in a recent interview with Forum News Service.

“I remember that well. The system fell down. It had a big role in changing the leadership in the ag department. And it turned over the leadership of the Bank of North Dakota, too,” she said.

At the time, farmers were struggling through years of uncertainty, drought and bank foreclosures not dissimilar to the Great Depression of the 1930s. Rarely had solid leadership in the agriculture department been more important.

ADVERTISEMENT

It was then, in 1986, that Jones and Herbert Thorndal, president of the state-owned Bank of North Dakota, believed they had found a lucrative Band-Aid in what ended up being a 20 million-pound potato deal to a tiny cooperative of farmers in northwestern Honduras called Ahpropapa.

The deal, initially not a secret, began after Jones and Thorndal put their names to two different promissory notes without authorization. Both notes were given to a never-before-heard-of company out of Miami called PetroLear Holdings Ltd., a Grand Cayman Island company.

Jones signed one for $300,000; Thorndal signed the other worth $1.55 million.

Backed by federal dollars from President Ronald Reagan’s Caribbean Basin Initiative, a 1983 aid program, what could go wrong?

Everything went wrong. The state never saw a single dime. The scheme to sell 4 million pounds of seed potatoes to Ahpropapa — the 700-grower, 1,000-acre Honduran cooperative — ended in vicious court cases, bribery, the Honduran Army marching on poor farmers to collect a North Dakota debt; two men behind bars, a lengthy FBI investigation, and a reputation that politicians in the Peace Garden State were “a bunch of idiots.”

If the plan had worked, the state would have seen a financial boon, Jones said at the time.

“There was a chance to make a hell of a lot of money, but we blew it,” he said in a Forum article about a year before he suffered a stroke the day after he lost his bid for reelection in 1988.

This article is based on articles from The Forum, Forum archives, North Dakota State University Archives and the Bismarck Tribune, as well as an interview with Vogel.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Caribbean beckons

In 1985, North Dakota wanted to compete for agricultural products in the Caribbean against the Dutch and the Canadians.

The initial plan was to take advantage of President Reagan’s Caribbean Basin Initiative, which provided federal dollars from the U.S. Agency for International Development to increase trade and promote development in that region.

Laurence “Laurie” McMerty, the Agriculture Department marketing specialist at the time, described as an “overly enthusiastic” and yet “very nice, likable guy,” by people who knew him, became the “prime architect” of a scheme to focus on Costa Rica, Guatemala, the Dominican Republic and Honduras.

“By chance, a marketing agency representative from Miami, Gabriel Nemeth, accompanied the Costa Rican delegation” to North Dakota to pay him a visit.

The stage was set, but nine months later, Nemeth’s company was absorbed by PetroLear, according to a 1986 story published in The Forum.

Rubber stamps

Jones was described by Vogel as a “handsome guy, who was slated for big things,” but was a hands-off administrator who kept a lax system where nearly every desk had a copy of his rubber signature stamp.

ADVERTISEMENT

At the beginning of Potato-gate, Jones said he didn’t remember approving the $50,000 note, which later put doubt in Vogel’s mind about Jones’ involvement in the scandal.

“Every secretary in the office had a signature stamp. Whether he did or didn’t (sign), he had a lax system of administering, there’s no doubt about that,” Vogel said in an interview with Forum News Service. On her first day in her predecessor’s chair as agriculture commissioner in 1988, she refused an order for additional signature stamps, choosing instead to personally read and sign every letter and contract herself.

“He got scammed, and one of the other things that was really embarrassing was that Laurie was on some south sea cruise, some free trip, that these scammers had given him. And for the Bank of North Dakota, the rumor I heard was that Herb Thorndahl and Laurie were going to go off and create this export company,” Vogel said.

The Honduras potato deal was a dipping of the toes into the international trade market for McMerty and Thorndahl, Vogel said. On the taxpayers' dime, they could develop contacts and learn the ropes of international trade.

“They were going to start an export company and go off and get rich,” Vogel said.

‘Bunch of idiots’

Although PetroLear was struggling financially in 1986, William Messner, chief of the Miami-based company, played his part as a legitimate businessman convincingly to Jones, McMerty and Thorndal.

The chain-smoking, shaggy, Marlboro-man-lookalike swept the delegates off their feet in a whirlwind of promises. He wined and dined them, offered expensive cruises, and at one point, he even introduced them to Central American leaders like El Salvador President José Napoleón Duarte.

ADVERTISEMENT

By June 18, 1986, the trio was sold on a deal to sell North Dakota seed potatoes to the Ahpropapa farming cooperative in Honduras. North Dakota had entered the world of international trade — for the first time with potatoes — and would be competing against countries like the Netherlands and Canada.

Messner started small. The first sale was 400,000 pounds of seed potatoes, and an eventual bill of sale from North Dakota worth $106,000.

But the Honduras cooperative wanted more, and in the end, the order increased to 20 million pounds. Messner agreed to withhold service fees if the state would provide him a line of credit. Upon completion of the deal, he would be entitled to the agreed-upon commission, around $90,000.

Something prompted Jones to look into PetroLear and Messner’s background, and on June 30, 1986, he hired a private detective and former FBI agent, William Butcher, to investigate.

By the next day — two months before Butcher’s report was finished — Messner arrived in Bismarck, and Jones signed the promissory note worth $300,000.

Twenty days later, Messner used $5,000 and a leased PetroLear car to grease the palms of bank officer Alfredo Velasco, and cashed the note for a discounted $264,000 at the American Express Bank International of Miami.

He then traveled back to North Dakota on Aug. 10, 1986, and met with Thorndal at a Bismarck hotel, who signed over the second $1.55 million promissory note.

“What he saw in there was an opportunity to make a __ of a lot of money,” the Bismarck Tribune quoted former PetroLear employee Robert Rivera (the blanked-out word was presumably profanity). He believed Messner needed the money to cover huge credit card bills and that he was overcharging the state of North Dakota for his services.

ADVERTISEMENT

The “flamboyant mastermind behind North Dakota’s failed Central American potato sale, was a ‘con of cons,’ " The Bismarck Tribune reported.

Messner enjoyed keeping his secretary happy with gifts; and liked good, expensive food. After cashing the first note, he laughed at Jones, McMerty and Thorndal, calling them bumpkins and saying he now had “the papers to rape, steal and pillage” North Dakota.

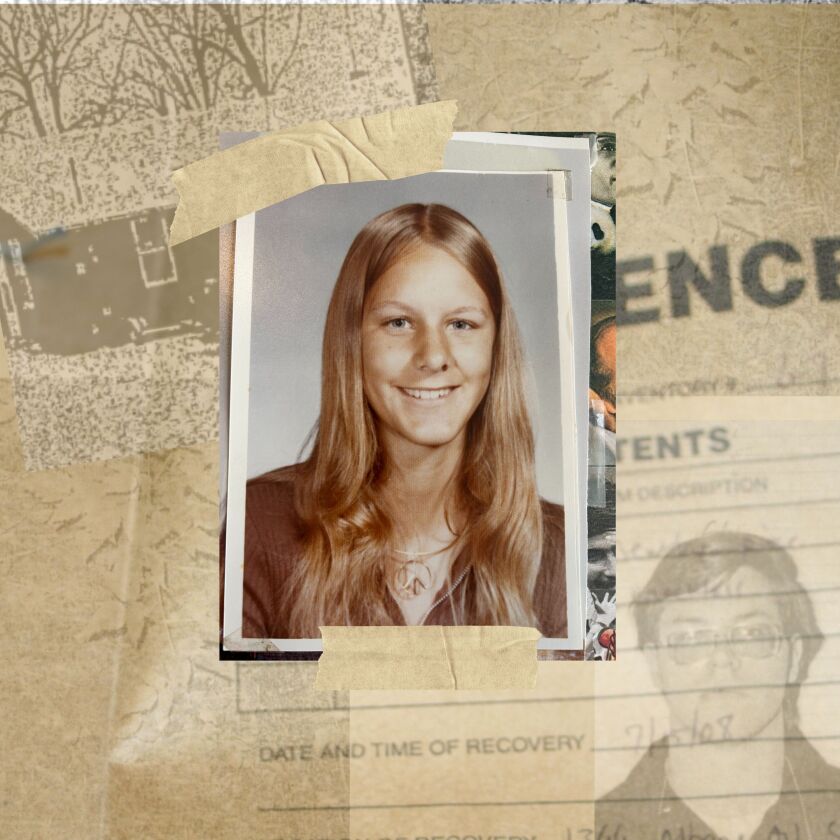

Perhaps to keep Jones deeper in his pockets, Messner arranged for a woman named Pam Pulkrabek to become involved with Jones, and together, they flew to Denver in July 1986 to meet Messner at PetroLear’s expense, according to articles in The Forum and The Bismarck Tribune. Jones said the trip was to iron out details of the deal and considered Pulkrabek an employee of PetroLear.

Pulkrabek said she was involved in a personal relationship with Jones, and was hired by PetroLear to open an office in Bismarck.

Jones refused to talk further about his relationship with Pulkrabrek.

A lengthy investigation by the FBI showed that Messner didn’t keep his glee secret. Former PetroLear employees called the North Dakota potato deal the “con of cons.”

“I was very much aware of what was going on there and… I thought that the officials of the state of North Dakota must be pretty stupid. I couldn’t understand how a deal like this could go down,” Raymond Greiner, a longtime friend and employee of Messner’s, said in a 1987 Bismarck Tribune article.

“His attitude towards North Dakota was along these lines… you have a bunch of idiots there so it’s easy for me to walk all over them,” Greiner said.

ADVERTISEMENT

Potato-gate unravels

A month passed by the time North Dakota Attorney General Nicholas Spaeth found out about the promissory notes. A CitiBank employee called Spaeth on Aug. 15, 1986, questioning the validity of the $1.55 million note signed by Thorndal.

Two years into his first term in office, Spaeth launched an investigation into the potato sale, saying Jones and Thorndal did not have the authority to issue the notes.

Thorndal resigned as president of the Bank of North Dakota.

Under mounting legal pressure, Messner returned the $1.55 million note to the state, but not before trying to sell it to American Express and then to CitiBank, which in turn locked his bank accounts.

Spaeth grilled Jones in an interview that was supposed to last an hour, but Jones walked out after 20 minutes, saying he wanted to talk to an attorney.

“He started asking questions like a prosecuting attorney. Spaeth was firing questions at me like I was on a witness stand,” Jones said in 1986.

Jones believed he did nothing wrong, but he acknowledged that he mistakenly believed that the promissory notes were not negotiable.

“I was not lily-white,” he said in 1986.

Jones, the State Industrial Commission, the state Export Trade Company, and even farmers across the state wanted the deal to go through, and they worked toward ensuring the potato deal’s success. Jones and Thorndal were cleared of legal wrongdoing, but were kept on a judicial leash for being held fiscally responsible.

Eventually, the state decided that the $1.55 million note would be paid in five annual installments as long as Messner was able to deliver in lining up other sales of state products overseas, Jones said.

After all, Messner was a big help as he was introducing them to government ministers, said Jones, who at the time pointed to a photograph of himself talking to the El Salvador president.

It was about this time when Butcher’s investigative report on Messner finished, and it came back empty. The company had no credit experience. Messner had no credit.

In desperation to find something, Butcher secretly went to a friend, Ward County Deputy Sheriff Art Olson, and ran an illegal NCIC check.

Again, empty.

“You might not find anything, but part of the reason for that is I have nothing to hide,” Messner said during a phone interview in 1986. He denied using an alias. All that detectives could find out about Messner was that he was a Canadian citizen, lived in Cayman Islands, and did not have any U.S. credit cards. He also had no criminal record.

Spaeth declined to file criminal charges against private eye Butcher.

Editor's note: This was Part 1 of a two-part series of articles about “Potato-gate.”Part 2 will publish next week and you'll be able to find it in The Vault.