Development initiatives aligned with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are counterintuitively relying on the same economic growth that leads to unsustainable development. Societies and policymakers need to examine alternative ideas and approaches to achieve sustainability.

—

Sustainability in human development is a necessity. In the modern world, we can no longer require populations to stay within their ecological means without jeopardizing the wellbeing of those that come after. Within international development, sustainability is defined as the long-term viability of both human development – allowing current and future generations to improve their social conditions and pursue aspirations – and Earth’s diverse range of ecosystems that make development possible.

Economic growth, historically touted as the engine of human development, has disproportionately benefited a handful of high-income countries (HICs) at the expense of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and the environment. Extreme poverty and socioeconomic gaps persist, while natural resources dwindle and the global climate changes.

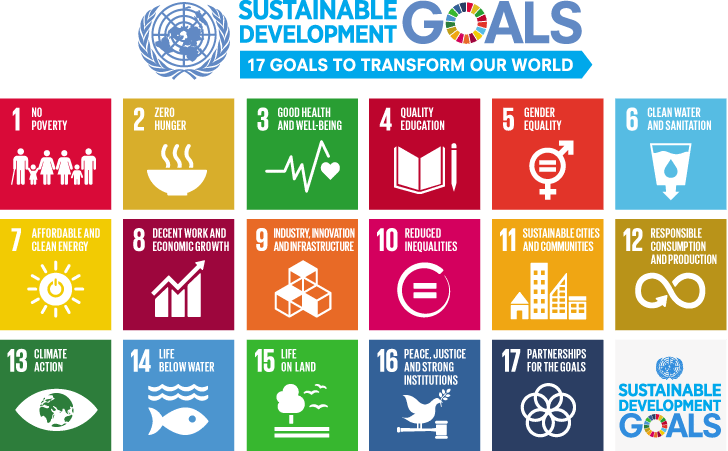

Today, the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) have taken on a central and influential role in defining the global path to sustainability. Adopted in 2015 by 191 UN member countries, the 17 goals and 169 individual targets call for integrating social, economic, and environmental priorities and serve as a framework for state governments, NGOs, development agencies, and the private sector to implement sustainable practices.

Unfortunately, the goals have proven to be optics over substance and have limited transformational impact. Conflating sustainability with progress in areas like eco-efficiency, the SDGs counterintuitively incentivize unsustainable development by relying on economic growth to meet their targets.

Alternative ideas and frameworks for sustainable development are numerous and potentially more fruitful; they not only offer novel approaches to address the complex challenges of development but also bring renewed perspectives and creative policy innovations that look beyond the SDGs and their growth-oriented development, contributing to humanity’s continuing pursuit of sustainability.

You might also like: What Is Sustainability and Why Is it Important?

In What Ways Are the SDGs Unsustainable?

Since first referenced in the context of development in 1972 by Barbara Ward in the book Only One Earth: The Care and Maintenance of a Small Planet, sustainability has sought compromise between economic growth and conservation.

When the Brundtland Report was issued 15 years later in 1987, calling for nations to re-evaluate their development models to preserve planetary support systems, there was wide acceptance that Earth lacks the carrying capacity to extend the full range of material wealth currently experienced by a handful of privileged nations to future generations. But since much of the world’s population still had not met all its basic needs, the Brundtland Report concluded that sustainable approaches to development should not prohibit development in LMICs. Rather HICs should do their equitable part and design development strategies decoupled from overexploitation of natural resources.

This idealistic but unworkable model of self-regulated goodwill and altruism among developed countries that have long benefited disproportionately from unsustainable growth laid the foundation upon which future international efforts of sustainable development were built.

In 2000, the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) called for eradicating extreme poverty and hunger while ensuring environmental sustainability by 2015. And while those subsequent 15 years saw measurable reductions in poverty – much of it attributed to the economic growth of China and southeast Asia, it also saw global emissions of carbon dioxide increase, an estimated 5.2 million hectares of forest lost, marine fish stocks decline to below safe biological limits, and increased extinction rates; all while developed countries continued to grow their populations and economies, unwilling to change or compromise their development models.

The 17 SDGs were announced in 2015 to supersede the MDGs and renew the call for reducing social inequality and protecting the environment. With these goals, the UN was resigned to the model of growth economics driving development, accepting (if not leaning into) the inequitable reality of development. Even making growth an explicit goal, as captured in Goal 8: ‘Decent Work and Economic Growth’.

With the release of the SDGs, the UN also advocated for an increase in private sector engagement. Initiatives like the UN Global Compact and Impact 2030 call for market solutions, private investment, and technology innovation to support sustainability. The outcome was a steady stream of consumer products that do not shy away from branding themselves as “sustainable”; products such as water-efficient fixtures and biodegradable bottles that prioritize discretionary consumption over protection of natural resources and environmental conservation.

Why Isn’t Eco-Efficiency the Same as Sustainability?

While sustainability is a balancing act between social, economic, and environmental needs, there is no definite prioritization between these three dimensions. Of the three, economic growth tends to deprioritize environmental concerns, placing the burden on the free market to weigh the environmental and social impacts of economic choices. This results in sustainability being redefined by markets. Instead of decoupling growth from development, the focus falls to how efficiently dwindling natural resources can be used to achieve development, a concept known as “eco-efficiency”.

Eco-efficiency is admittedly a practical way to moderate environmental stressors in the short term, focusing minds on reducing the resource intensity of economic activities. Increasing recycling rates and renewable energy, while reducing the amount of water, minerals, and trees utilized to produce goods and services are tangible and quantifiable actions. Consumers will regularly see companies label their products as sustainable when using less plastic for packaging, powering their factories with renewable energy, or producing clothes from cotton, hemp, or bamboo.

But eco-efficient products do not achieve sustainability on their own in a growing economy, failing to reduce aggregate demand for resources (nor do they diminish inequality and extreme poverty). For instance, if an individual company uses 50% less plastic per unit of output (50g instead of 100g for packaging) the eco-efficiency is clear. However, if the intention is to grow and increase sales, they will quickly require more plastic. Where 100 units of packaging requires 5,000g of plastic, 300 units requires 15,000g, 1,000 units requires 50,000g. Scale that up to an entire economy where development relies on growth and it becomes clear that eco-efficiency is not a substitute for sustainability.

Water efficient fixtures and biodegradable water bottles are similar examples, both requiring new manufacturing capabilities that rely on land, water, and other natural resources to operate. The intent is not to reduce the total number of products sold, just to use slightly fewer inputs to make them. In the pursuit of sustainability and by embracing consumption-based growth, the SDGs have come to incentivize unsustainable practices.

What Are the Alternatives for Sustainability?

While the SDGs are not guarantees for sustainability, they do serve as a framework for pursuing development in a conscientious way. The SDGs, like the Brundtland Report and the MDGs before them, are a stepping stone to sustainability. Their limitations and disingenuous facades create the impetus for alternative ideas to achieve balance with the planet’s ecosystems.

Well-known concepts such as steady-state economics – which advocates for keeping populations and economies at a fixed size, and “degrowth” – where the objective is to shrink the overall economy to minimize the use of natural resources, can be insightful, requiring thoughtful reflection on humanity’s impact to planetary support systems, but are not viable in the short-term. An attempt to hold economies at a constant size, or actively decrease output, would require a rapid and drastic transformation of how societies are organized. And while falling fertility rates globally may be a form of degrowth or steady state, there is no guarantee the trend won’t reverse at some future point, and neither is there a foreseeable end to increasing consumption in a shrinking population, given the breadth and depth of unmet needs in developing countries.

More practical movements, like Beyond GDP, view common economic metrics like Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as poor measures of development, advocating for governments and policymakers to place greater emphasis on human and environmental wellbeing.

The Genuine Progress Indicator tries to measure the social and ecological impacts of growth, calculating pollution and inequality as a loss to national value; countries that aggressively regulate pollution and inequality have a relatively higher value then those that do not. The UN’s Inclusive Wealth Index tries to measure the value of social and environmental assets of a nation, which often go unmeasured in economic transactions, while the Human Development Index (HDI) examines social criteria such as health and education for assessing human development. However, many of these metrics do not replace GDP but rather augment it, layering new dimensions that can be inadequate proxies themselves or inconsistently measured between countries and making it difficult to compare across jurisdictions. And while they struggle to address aggregate consumption, their focus on non-economic factors of development is a valuable contribution to sustainable thought. Additional work will be needed before a sustainability-centric metric is widely accepted and adopted.

Circular economy puts carrying capacity at the forefront, offering a model of “sharing, leasing, reusing, repairing, refurbishing and recycling existing materials and products as long as possible.” In reducing the amount of virgin natural resources needed for development, a circular economy seeks to reduce the stresses on carrying capacity through a constant recycling of materials. In 2020, the European Union adopted the Circular Economic Action Plan (CEAP) aimed at reducing waste and increasing recycling in resource-intensive sectors such as textile, plastics, and construction. In the US, recent legislation such as the Inflation Reduction Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law advocate for a circular economy and include provisions encouraging waste reduction and recycling.

Doughnut economics attempts to push the circular concept further by incorporating social and ecological justice in a donut-shaped model. Where the outer layer is the ecological limits of nature, the inner layer symbolizes “the minimum social foundation necessary” for sustainability, and the center of the doughnut is where human development and the planet find harmony.

The challenge for circular economics is its emphasis on reducing waste and not growth. If every item is recycled, it would represent at best a steady state of a 1:1 replacement of products. If development continues to rely on growth, virgin natural resources will still be necessary. Doughnut economics as a conceptual model is utopian in nature and does not provide an actionable plan for reaching ecological harmony, making it impractical in the short-term for real-world applications.

One approach that could have an immediate impact on growth-oriented economies is granting non-human species legal rights. Recognizing the right of flora and fauna to exist without prejudice, thereby requiring environmental welfare be considered in all economic decisions. This idea is not new. The belief that the environment should enjoy constitutional protections influenced the establishment of Earth Day in the US – with personhood for the natural environment already enshrined with the laws of Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, and, to a lesser extent, New Zealand. It recently gained renewed attention when New Zealand’s Maori King Te Arikinui Tuheitia Park and 15 chiefs from Tahiti and the Cook Islands declared whales to have the same rights as people.

More on the topic: Nature Rights: What Countries Grant Legal Personhood Status to Nature And Why?

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, sustainability will require a shift away from the growth-at-all costs mentality of development. Each iteration of ideas, insights, and models that embrace sustainability free of a reliance on economic growth contributes to this future where human development and environmental preservation go together. The more these ideas spread, educating consumers, influencing policymakers, and informing economic decisions, the closer societies get to preserving the planet’s essential life-support systems while pursuing developmental aspirations.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us