What can Nevada learn from Georgia’s film industry incentives?

At the end of “Spider-Man: Homecoming,” Netflix’s “Stranger Things,” and dozens of other movies and TV shows, there’s a logo that has become familiar to cinephiles over the last decade: a Georgia peach.

It signals production was shot in the Southern state — and received tax incentives to do so.

Nevada could soon have a logo of its own rolling at the end of credits. In what may be the most captivating legislative proposals of the 83rd Legislative session, lawmakers are considering a move to expand the state’s film production tax credit program and get Hollywood looking east to its next door neighbor.

But it won’t be without some back-and-forth on the costly push to get soundstages in Las Vegas.

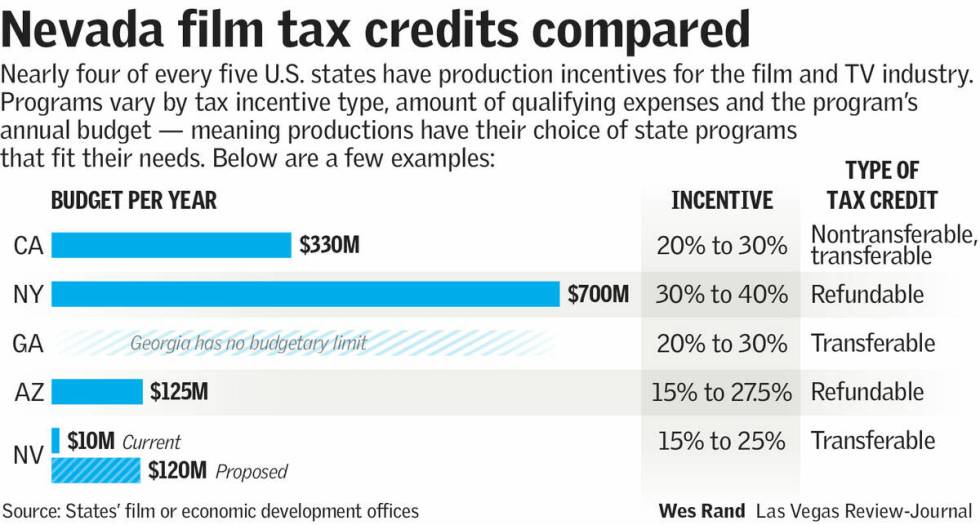

At a hearing in late February, Assembly members frequently asked bill sponsors and studio executives how Assembly Bill 238 compared with other programs, like the one in Georgia.

As lawmakers in Carson City consider a significant expansion of Nevada’s film production tax credit program, they can look east to see how the Peach State used tax credits to transform itself into a major hub for the television, streaming and film industries.

How the Peach State became ‘Y’allywood’

Georgia’s tax credit program was enacted in 2005, but a 2008 law massively expanded the law into what it is today.

The program includes a transferable tax credit of 20 percent of production expenses for eligible productions and an additional 10 percent credit if the production includes the Georgia logo on its project.

Applicants must spend at least $500,000 on payroll, materials and services purchased from a Georgia vendor to qualify for the tax credit. One or multiple projects done by the same production company can qualify if they are in the same tax year. Additionally, post-production work such as editing and special effects of Georgia-filmed projects can also qualify if done in the state.

Perhaps most notably, the program has no limit on qualifying expenditures, no compensation caps for freelance laborers — the most common form of employment in the industry — no caps on spending in Georgia, and it does not expire.

Georgia film production is expected to generate nearly $1.32 billion in tax credits in the 2025 fiscal year, according to a December 2023 state audit of the program. Nevada’s AB238 proposes tax credits totalling up to $1.65 billion over 15 years.

But at least in the case of Georgia, there’s a twist: Since production companies don’t necessarily make a taxable profit, most Georgia tax credits are sold to other taxpayers to lower their tax burden.

Carlianne Patrick, an associate professor of economics at Georgia State University, said the ability to sell the tax credits, even at a slight discount, is part of why the program is so popular.

“Transferability is actually the key in a film tax credit, because the vast majority of film productions will not have a state tax liability,” Patrick, the lead author of the audit, said. “In Georgia, it’s because most of it is going to be coming from income tax, and there won’t be a state income tax liability for the production.”

In fact, Georgia’s audit found between 2015 and 2022, an average of 63.5 percent of the tax credits claimed were from individual filers — meaning more credits were sold than used by the studios that received them.

Fueling Peach State production

Georgia’s film tax credit program saw steady growth after 2008 but saw a surge in production and the number of projects starting in the mid-2010s. The number of big-budget productions rose when Atlanta Filmworks opened 36,000 square feet of studio space in 2013 and Pinewood Atlanta Studios — later renamed Trilith Studios — opened and began producing Marvel Studios superhero movies in its 717,150 square feet of space in 2014.

In 2019, Tyler Perry Studios moved to 330 acres on a former Army base in Atlanta. The sprawling studio lot includes 50,000 square feet of permanent sets, including a replica of the White House, a mansion and a mid-century American diner.

Film industry advocates say none of that investment — roughly $1.28 billion spent erecting purpose-built studios, renovating existing buildings into studios and making other expansions between 2012 and 2022 — would have occurred without the tax credit program. Kelsey Moore, executive director of the Georgia Screen Entertainment Coalition, said the major capital projects and influx of industry workers came after several years of the unlimited program.

“That tax incentive was absolutely critical in Georgia’s rise to become this production powerhouse. In anecdotal evidence, Georgia’s film office opened in 1973 when the movie ‘Deliverance’ was filmed here,” Moore said. “But (in recent years) we do more production in a single year than we did in the first 50 years of the film office.”

Making sense of the economic impact

The economic impact of the film industry is hard to ignore, Moore argued. Her organization commissioned a 2023 study by international consulting firm Olsberg SPI that reported film production added just over $7.6 billion to the state’s economy in 2022. That measure included direct, indirect and induced impacts — meaning the economic output of the production companies, support businesses and the effect of workers’ wages spreading and multiplying in the local economy. Adding in the value of studio construction investment boosted the impact to $8.5 billion, the report said.

The report said that for every tax credit dollar in the state that year, Georgia saw a $6.30 boost to its economy. Direct return on investment alone reached $3.70 for every dollar of tax credits, according to Olsberg SPI.

A state audit suggests a smaller impact. A Georgia State University research team found the gross economic impact from film tax credit was about $4.5 billion in 2022, according to the report. The report also noted that the employment numbers do not often reflect full-time, permanent jobs; many industry workers are freelancers.

Moore said state audit results that showed Georgia would earn only 16 cents in tax revenue for every dollar of tax credit granted in 2025 are missing the point of the program.

“I think anyone knows you don’t create a tax incentive to create more tax dollars,” she said. “You create a tax incentive because you want some aim — whether it’s to create an economic boost, create jobs, attract an industry.”

What about Nevada?

Nevada’s chance to get a Hollywood nickname of its own could come out of legislation in consideration at the Legislature this session. Two bills propose expanding the state’s existing tax credit program and tying the new production tax credits to the construction of a studio campus in Southern Nevada.

AB238 was the first to have a hearing in late February. The bill is backed by Sony Pictures Entertainment, Warner Bros. Discovery and Howard Hughes Holdings, which owns the land for the proposed studio near Flamingo Road and Town Center Drive. At the Feb. 27 hearing, lawmakers asked the firms’ representatives and bill sponsors Sandra Jauregui and Daniele Monroe-Moreno, both Clark County Democrats, about the economic effects and if the proposal would benefit Northern Nevadans.

Unlike Georgia’s program, both AB 238 and Senate Bill 220 limit the amount of available tax credits and ends the program after 15 years. AB 238 would expand the tax credit program to $120 million annually, with $25 million set aside for nontransferable production credits for projects outside of the Summerlin studio. (The bill was originally introduced at $80 million annually, but the bill sponsors said during the hearing they planned to introduce an amendment changing the total.)

Senate Bill 220, sponsored by state Sen. Roberta Lange, D-Las Vegas, would expand the state’s program to up to $83 million annually for a studio project based at the Harry Reid Research and Technology Park near Sunset Road and Durango Drive in southwest Las Vegas. It includes a ramp-up period with up to $63 million in annual tax credits available for construction during the development period, as well as $15 million for “noninfrastructure” transferable tax credits.

Nevada’s existing program is capped at $10 million annually, with a maximum of $6 million per production.

Patrick, the Georgia State professor, said she thought Nevada’s expanded proposals are unique in tying the tax credit to a capital investment. In AB 238, the tax credits do not become available until $400 million is spent on construction.

Tax credits in both bills are transferable, just like in Georgia. What’s different in the Nevada bills’ provisions is that they allow companies to use the credit to reduce gaming license fees, the taxes insurance companies pay on premiums they receive and on the state’s Modified Business Tax.

Though not in its original law, Georgia’s Legislature responded to the growing industry by allocating funds for certification programs. The Georgia Film Academy is run through the state’s higher education system and available through 28 university and technical colleges in the state.

That’s different than what is proposed in Nevada. Both the Assembly and Senate bills require educational and vocational training facilities associated with the project. Jauregui’s bill would require at least $8 million for a training site and $6 million for the Clark County Redevelopment Agency’s arts and cultural programs, as well as small business support related to productions. Lange’s bill would establish the Nevada Media and Technology Lab at the UNLV research park site.

Also notable in Nevada’s bills is a requirement to employ Nevadans. AB238 would require at least half of principal photography days to take place in Nevada, with additional tax credits available if Nevadans make up at least half of “below-the-line” workers, who have technical roles like lighting grips and camera operators.

In a March 19 text, Lange said there will be a hearing for SB 220, which is expected to partner with Birtcher Development and Manhattan Beach Studios Group for its proposed studio project. No date has been announced.

Lange first proposed the expanded tax credit idea, tied to a studio and new educational facilities, during the 2023 session. But that proposal sought to bring $190 million annually into the credit program, enough for multiple studios. It did not receive a vote then.

With so many factors involved in the industry’s impact – and measuring that impact – Patrick said it can be a challenging decision for policy makers.

“It’s their choice, but I think it’s important for them to think about those sorts of things when they’re deciding what trade-offs they want to make, because at the end of the day, states do need to have balanced budgets,” Patrick said. “So, even if it’s purely forgone revenue, that’s still foregone revenue that some fraction of which at least could have been used on other things.”

Trade-offs haven’t stopped Georgians. A 2024 effort to limit the amount of annually available film tax creditsfailed in the state’s legislature.

Patrick said many Georgians are all-in on their project. Part of it, she said, could be due to the “glamour of Hollywood.”

“I know when it started in Atlanta, people used to gather around and be like, ‘There’s Will Ferrell in the park!’ And now, nobody cares —‘Ugh, they closed the road again,’” Patrick said. “Initially, people see it as a glamorous, high-profile industry that can raise the profile of the state.”

To film industry advocates, keeping the incentive competitive is critical to the longevity of the industry — at least in Georgia.

“We’ve seen some states try it, but if they’re not all in, they’re not seeing the kind of return that we are seeing,” Moore said.

Contact McKenna Ross at mross@reviewjournal.com. Follow @mckenna_ross_ on X.