A Theory of Calibrated Fiduciary Duties in Firms

At the heart of the laws of firms lies an unsolved enigma: Although all owners presumably desire maximal profit irrespective of the form of firm, the rules of fiduciary duty diverge, as if the law seeks discretely disparate managerial behavior and thus qualitatively different business outcomes for each form of firm. The differences are not subtle shades of refinement, but quantum contrasts of discrete legal states. The law shuffles, reclassifies, and relocates core elements of the duty of care and the concept of good faith uniquely in each form of firm. Why? Despite apparent differences in legal expressions, a single fiduciary rule governs all forms of firms. My article, A Theory of Calibrated Fiduciary Duties in Firms, 51 Journal of Corporate Law (forthcoming 2026), theorizes the idea of calibrated fiduciary duties, which explains why the law does and should vary the fiduciary standards of conduct in agency, noncorporate firms, and corporations.

![]() The theory of calibrated duties unifies the fiduciary concept across the laws of all firms. The law cannot state a uniform standard of conduct because forms of firms do not share a single optimal welfare state. To induce their varying optimal ends, the law must uniquely calibrate fiduciary duties. This Article advances two important insights: bilateral relational risk is the idea that owners and managers are exposed to an intrinsic risk arising from their relationship, comprising of the risk of agency cost for owners and the risk of liability for managers; and intermediated risk preference is the idea that the personal risk preferences of owners and managers are intermediated through the firm and the rule of fiduciary duty such that managerial actions, incentivized as such, actuate an intermediated risk preference that achieves an optimal welfare state for each form of firm.

The theory of calibrated duties unifies the fiduciary concept across the laws of all firms. The law cannot state a uniform standard of conduct because forms of firms do not share a single optimal welfare state. To induce their varying optimal ends, the law must uniquely calibrate fiduciary duties. This Article advances two important insights: bilateral relational risk is the idea that owners and managers are exposed to an intrinsic risk arising from their relationship, comprising of the risk of agency cost for owners and the risk of liability for managers; and intermediated risk preference is the idea that the personal risk preferences of owners and managers are intermediated through the firm and the rule of fiduciary duty such that managerial actions, incentivized as such, actuate an intermediated risk preference that achieves an optimal welfare state for each form of firm.

Fiduciary Rules in Firms

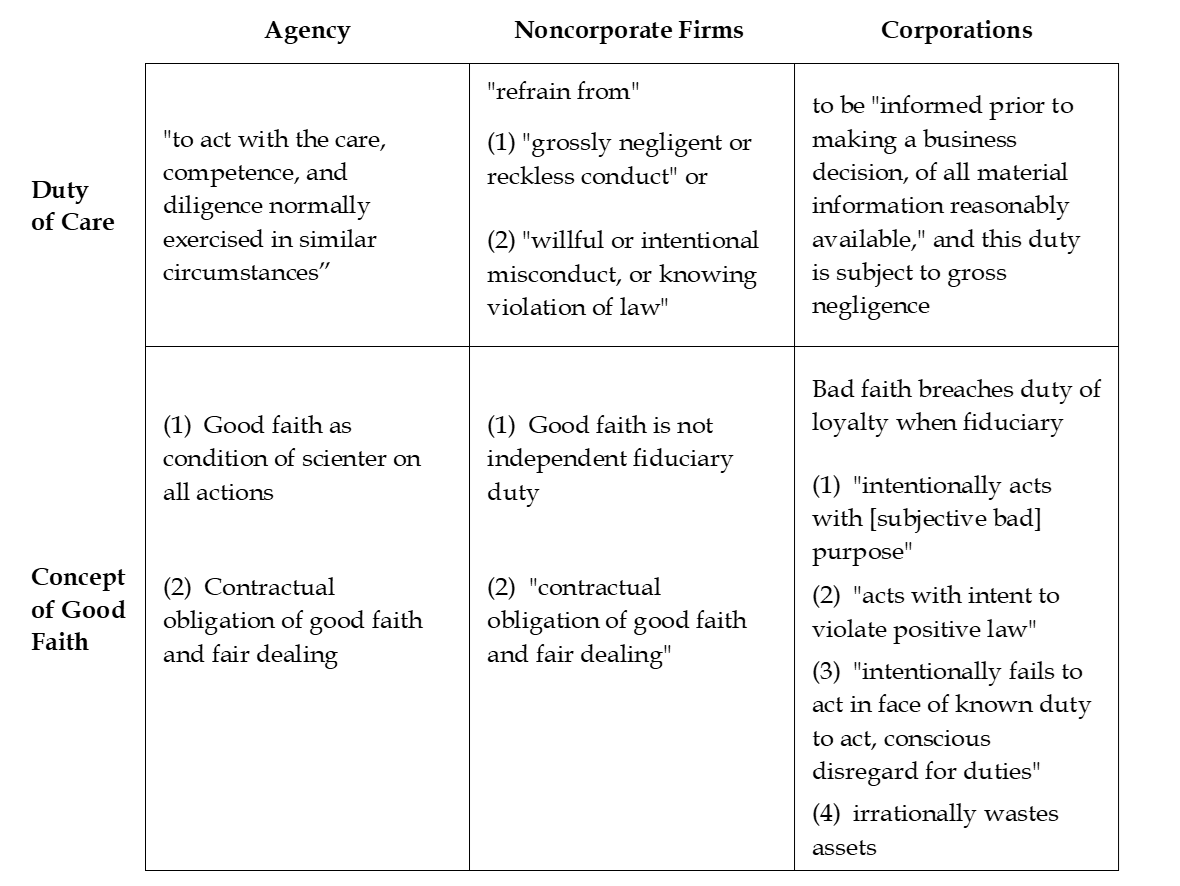

The duty of loyalty in classic form proscribes all types of conflict of interest dealings. Since its rationale is broadly generalizable and self-evident, it is functionally identical in the laws of firms. However, the duty of care and the concept of good faith have markedly diverged along the multiple pathways of agency, noncorporate firms, and corporations. (An agency relationship is not a firm, but it provides a useful reference as the elementary fiduciary relationship.)

The scope of the duty of care is the broadest in the law of agency, then narrows in the law of noncorporate firms, and narrows further in corporation law. An agent has the fiduciary duty to act with the reasonable care and competence, which incorporates a tort-like substantive standard. The laws of noncorporate firms lowers the standard of conduct to refraining from engaging in grossly negligent or reckless conduct, willful or intentional misconduct, or a knowing violation of law. Corporate law states the lowest standard of conduct, the duty to be informed in decisionmaking, subject to the grossly negligent standard. The concept of “substantive due care” is “foreign” to corporate law.

The concept of good faith also diverges. A fiduciary must act in subjective good faith. Because agency relationships and noncorporate firms are contract-based, the contractual obligation of good faith and fair dealing attaches. In corporate law, the contract rule does not play a prominent role. Rather, the concept of good faith is a component of the duty of loyalty. Certain categories of bad acts have been classified as bad faith acts, thus breaching the corporate duty of loyalty. Of course, the substance of these bad acts could occur in the noncorporate context. In this regard, we see a perplexing overlap in laws. All forms of corporate bad faith can be fitted into the noncorporate duty of care.

The duty of care and the concept good faith have branched off into winding paths that intersect and diverge at different places. These differences are not small refinements or marginal adjustments that may be necessary to harmonize legal vocabulary or structural aesthetic (see table below).

In summary, the laws of firms differ with respect to the scope of misfeasance (vis-à-vis malfeasance implicating the duty of loyalty in classic form). The standard of conduct is the highest in the law of agency and the lowest in corporate law. The law shuffles, reclassifies, and relocates elements of the duty of care and the concept of good faith in the forms of firms. What is the theory of calibrated fiduciary duties in firms? Two principles—bilateral relational risk and intermediated risk preferences—govern, and their interplay yields four factors that calibrate the standard of conduct in all firms.

Bilateral Relational Risk

As Rome is the eternal city, profit is the eternal motive. Based on this axiom, a natural intuition follows: If maximal profit is the end in all for-profit firms, and if fiduciary duty serves this motive, the standard of conduct should converge to a single expression that would optimally produce maximal profit irrespective of the form of firm. This reasoning, however, is wrong in legal fact and in theory. The motive force of maximal profit is irrelevant to an inter-form theory of legal divergence. We search not for a constant, but for a variable. Optimal welfare must account for exposure to risk and risk preferences. Risk is the conceptual variable. Financial economics has long given us the insight that profit and risk are tradeoffs. The core managerial function is to arbitrate this duality. Thus, the optimal welfare state varies among forms of firms.

When managers and owners venture together, they are exposed to another form of risk. Bilateral relational risk is the intrinsic risk that arises from the relationship between owners and managers as they venture together and are bound in a legal relation. The most familiar form of this risk is agency cost, which is simply the bilateral relational risk that runs directionally to owners. Agency cost, a long preoccupation in economic and legal literature, tells only half the story.

The untold half of the story is the manager’s risk of loss from liability to owners and the firm. Of course, we have always known about the fact of liability ever since the law imposed fiduciary duty and liability for breach (e.g., Keech v. Sanford and Smith v. Van Gorkom), but we have not connected the owner’s risk of agency cost to the manager’s risk of liability under a common theoretical framework of relational risk and firm welfare.

Fundamentally, a fiduciary relationship means that the fiduciary and the obligee have assented to be bound together in legal duty and relation. The orthodoxy of agency cost skews the perspective. We must consider relational risk holistically. Like profit and risk, bilateral relational risks are conjoined. Owners and managers mutually benefit each other, but also impose bilateral costs. When owners allege that managers bungled or betrayed trust, managers are exposed to liability. This risk of loss is the bilateral relational risk that runs directionally to managers.

Intermediated Risk Preference

When venturing together, owners and managers do not shed their innate human nature. They start from the initial position of risk aversion. But this preference is not always expressed in managerial actions because personal risk preferences are intermediated through the form of firm to produce managerial actions that express the firm’s intermediated risk reference. Expressed risk preference is not a constant but a variable, reflecting each form of firm’s optimal welfare level of risk taken and profit expected. Thus, intermediated risk preference is actuated by a set of rules that incentivizes managerial actions to achieve this welfare level in spite of any innate personal predilections.

An agency relationship is not envisioned as a business venture. The core activity of an agency is not profit making, but instead representation. The motive force is fidelity to instructions and intent. From this perspective, agency is not fundamentally a risk-taking activity at all. Success is not measured by ex ante profit but by ex post accomplishment of intended instructions. An agency relationship is not and does not impart firm intermediation. The natural preferences of individuals govern. Therefore, risk aversion is the strongest in agency.

Noncorporate firms are prototypically smaller business ventures in which owners have closer proximity to the business and the manager. They are less diversified in terms of products and business lines than public corporations. Owners often have their principal economic livelihoods tied to the firm, unlike public shareholders. They often manage the firm or work there as employees. Together, these characteristics suggest that owners are more sensitive to business risk because bad outcomes will sting more. Therefore, intermediated risk preference moves toward risk neutrality, but still retains some degree of personal risk aversion.

Public corporations are characterized by large, complex ventures. They have the most owners, the biggest capital cushion, the greatest diversity of businesses, the most specialized managers, and the most complex business structures writ large. They can embrace risk neutrality, which is the ex ante profit maximizing strategy. Unlike owners in noncorporate firms whose economic livelihood are frequently tied to their firm, public shareholders can easily diversify away their exposure to the unique risk of the corporation. Therefore, the corporate form intermediates risk preference in favor of risk neutrality.

Theory of Calibrated Fiduciary Duties

When risk is the variable, a single uniform optimal state of welfare does not exist. The internal dynamic between bilateral relational risk and intermediated risk preference is critical to our understanding of fiduciary duties, and it reveals an important insight: Given the unique structure and organization of each form of firm, the state of optimal welfare must vary with intermediated risk aversion that diminishes along the line of agency, noncorporate firms, and corporations.

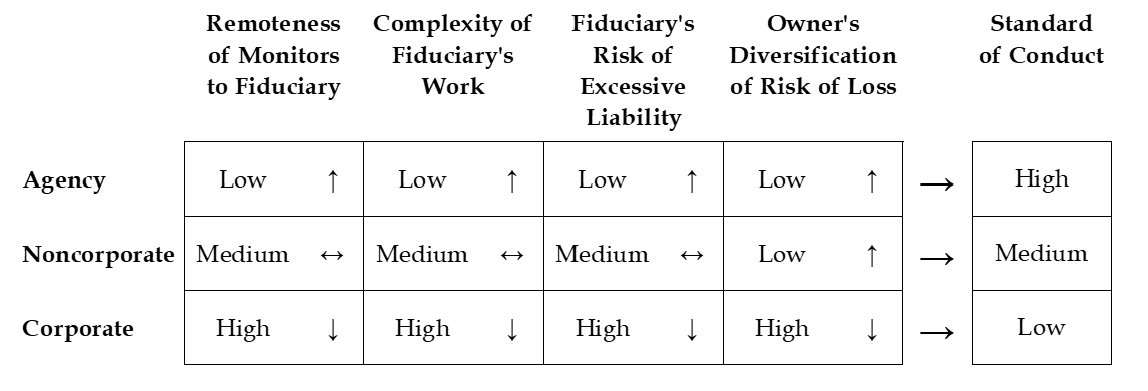

Based on the calculus of these two principles, this Article derives four factors of calibration, each affecting the standard of conduct to achieve unique optimal welfare states for forms of firms: (1) proximity of monitors to fiduciary; (2) complexity of fiduciary’s work; (3) fiduciary’s exposure to excessive liability; and (4) owner’s diversification of risk of law. Unique combinations of these factors in the forms of firms explain why the law varies fiduciary standards in forms of firms and why this variance is right. The ordering of the standards of conduct in firms is not random. Let’s synthesize the dynamics for each form of firm.

The law of agency states the highest standard of conduct. Agency is characterized by high degree of monitoring due to the close legal and working proximities between the principal and agent, the relative simplicity of the agent’s work, low risk of excessive liability for the agent, and the principal’s inability to diversify away the errors of the agent. Under these conditions, the principal can rationally demand a high standard of care. The agent will assent because she will likely meet the high standard due to high monitoring and low complexity, and even if she fails, her risk of excessive liability is low.

The law of noncorporate firms state an intermediate standard of conduct. Three factors of calibration weigh in favor of a lower of standard of conduct. Compared to agency, noncorporate firms exhibit more remote legal and working proximities among partners, more complex form of partners’ work in managing a firm, and a higher exposure to excessive liability in light of the fact that they manage a business venture. Like a principal in agency, a partner cannot diversify away the errors of other partners. An assessment of the four factors militates a lower standard of care.

Corporation law states the lowest standard of conduct. The legal and working proximities of monitors are most remote. The complexity of a manager’s work is the highest. Managers are exposed to the highest risk of excessive liability. Unlike principals in agency and owners in noncorporate firms, shareholders can diversify away the errors of fiduciaries in the public stock market. The fiduciary can rationally demand the lowest standard of care, and the obligee will assent. Policy can induce intermediated risk neutrality to maximize profit, achieved only when managers are incentivized through the lowest standard of conduct such that the risk of liability is the lowest.

The following table summarizes the four factors of calibration as they are applied to the laws of firms. The arrow in each box indicates the relative effect of the factor on the standard of conduct, consistent with the analysis above: indications noting ↑ for higher standard of conduct, ↓ for lower standard, and ↔ for intermediate (medium) standard.

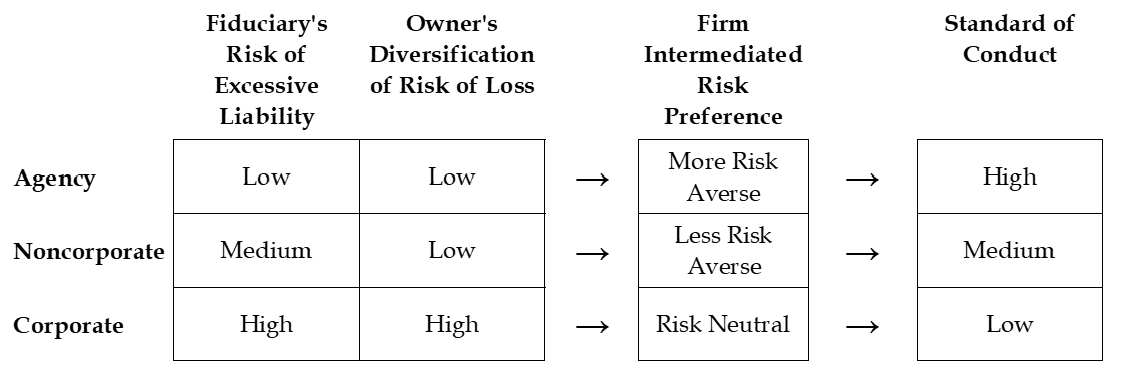

This Article also theorizes the connection between risk (i.e., bilateral relational risk and risk preferences) and the unique calibration of fiduciary duty. In agency, risk preference is not intermediated by a firm structure. Natural risk preferences govern, which we presume to be risk aversion. In noncorporate firms, the firm structure intermediates personal risk preference, resulting is less risk aversion. The dynamic of bilateral relational risk is this: Owners cannot diversify away his risk from the manager’s errors, and managers are subject to greater risk of excessive liability since they are tasked with managing a firm. The standard of conduct should be lower than that in agency. In corporations, the intermediated risk preference is risk neutrality. The dynamic of bilateral relational risk is this: Owners can fully diversify the risk of managerial errors, and managers are subject to excessive liability. The standard of conduct should be the lowest among the forms of firms. The table below summarizes how the effect of this dynamic on the standard of conduct.

Concluding Thoughts

The law does not assign random rules of fiduciary duty for each form of firm. It uniquely formulates standards of conduct for good reason. It has in mind specific needs. Initial intuition suggests that if maximal profit is a constant, and if fiduciary rules affect managerial actions toward the venture’s end, a unitary fiduciary rule and standard of conduct should govern. The law contradicts this easy intuition. It shuffles, reclassifies, and relocates elements of the duty of care and the concept of good faith. In doing this, it applies a single fiduciary rule. It uniquely calibrates each set of fiduciary duties and standards of conduct to fit the prototypical need of each form of firm.

Risk is the critical variable. The underlying principles of calibration are bilateral relational risk and intermediated risk preference. The internal dynamic of these principles in the forms of firms yields four factors of calibration. When these factors are applied to the structure and organization of the forms of firms, they produce varying standards of conduct that are unique to each form. The law as seen today comports with this theory. Lastly, this Article provides an important datum that corroborates the theory of calibrated fiduciary duties. It is an episode from the history of Goldman Sachs, which is its conversion from a private partnership to a public corporation at the end of the twentieth century.

Distribution channels: Education

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

Submit your press release